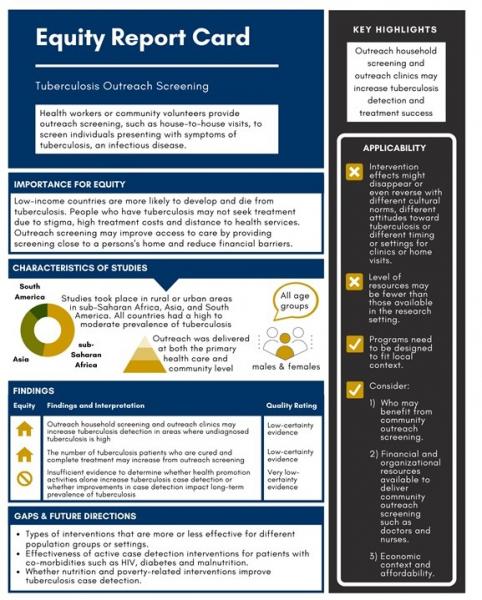

Outreach household screening and outreach clinics may increase tuberculosis detection

Why is increased tuberculosis detection important?

Tuberculosis is a chronic infectious disease that affects over 10 million people worldwide, with an estimated four million tuberculosis patients remaining undiagnosed each year. Over 40% of tuberculosis cases occur in India, Indonesia and China, while populations in some African countries have the highest rates of tuberculosis. In 2015, tuberculosis caused 1.8 million deaths. Undiagnosed tuberculosis is widespread in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and South America. Delayed diagnosis tends to result in poorer health outcomes and can increase transmission rates. People may delay seeking care owing to stigma associated with tuberculosis, uncertainty about how severe their illness is, as well as barriers to healthcare access such as distance and affordability. Tuberculosis outreach screening involves house-to-house visits by health extension workers or community volunteers, and can be combined with screening at schools and safe motherhood clinics. Outreach screening is also sometimes combined with printed leaflets promoting visits to a health clinic.

Does outreach and active case-finding increase tuberculosis case detection?

- House-to-house screening for tuberculosis may increase case detection in settings where undiagnosed tuberculosis is widespread (low-certainty evidence).

- Organizing tuberculosis diagnostic clinics closer to where people live and work may increase case detection in settings where undiagnosed tuberculosis is widespread (low-certainty evidence).

- There is insufficient evidence to determine whether health promotion activities alone increase tuberculosis case detection (very low-certainty evidence).

Equity – Does outreach work for the disadvantaged?

- The trials included in the review were conducted in a mix of upper-middle-income countries (Brazil, Colombia, South Africa), middle-income countries (Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Zambia), and three low-income countries (Ethiopia, Nepal, and Zimbabwe), in both rural and urban settings. Undiagnosed tuberculosis is widespread in each of these countries.

- Systematic household-based tuberculosis screening can reduce various barriers to accessing care, by providing the initial screening test at the patient’s home – this reduces the financial costs for the patient, reduces stigma, and increases patient awareness. It can also improve tuberculosis diagnostic skills among health workers through related training.

- Organizing mobile tuberculosis diagnostic clinics closer to where people live and work can reduce geographic and related financial barriers to access.

- Decreasing the time to diagnosis can reduce socioeconomic impacts of tuberculosis, such as reduced time off work and reduced loss of earnings.

- However, barriers to accessing tuberculosis diagnosis vary considerably between settings and accordingly, programs need to be designed to fit the local context.

Intervention delivery

- The interventions included in the review were any that aim to improve access to a tuberculosis diagnosis through diagnostic services at the primary health care or community level. These included educational or health promotion activities and outreach services using formal and informal health staff through clinics, mobile clinics, and house-to-house screening. The control interventions where either the standard care approach, or alternative interventions for improving access to a tuberculosis diagnosis.

- Comparison 1: Outreach tuberculosis screening (clinics or household visits) with or without health promotion activities versus no intervention.

- Comparison 2: Health promotion activities (ranging from mass media campaigns to local community-based activities) versus no intervention.

- Comparison 3: Staff training versus none.

- Comparison 4: Outreach tuberculosis screening versus health promotion.

- Comparison 5: Outreach mobile clinic (6th-monthly) versus house-to-house screening.

- Comparison 6: Active case-finding interventions versus no intervention.

- Comparison 7: Outreach tuberculosis services versus no intervention

Population and setting

- Participants were from all age groups in 12 countries with a high to moderate prevalence of tuberculosis, at the primary health care and community level.

Summary of Findings [SOF] Table: Tuberculosis outreach screening with and without health promotion

Patient or population: All age groups

Settings: Countries with high or moderate tuberculosis prevalence

Intervention: Tuberculosis outreach screening with and without health promotion activities

Comparison: No screening

Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects | Risk Ratio | No of Participants | Quality of the evidence | ||

Risk without outreach screening ± health promotion (Control) | Risk difference with outreach screening ± health promotion (95% CI) | |||||

Tuberculosis cases detected (microbiologically confirmed) | 90 per 100,000 | 112 per 100,000 (77 to 161) |

|

|

| |

Default within first two months | 16 per 1000 | 12 per 100 (8 to 15) | RR 0.67 (0.47 - 0.96) | 849 (3 cluster RCTs) | Low 1,2,5 due to imprecision | |

Treatment success | 78 per 1000 | 83 more per 100 (78 to 90) | RR 1.07 (1.00 - 1.15) | 849 (3 cluster RCTs) | Low 1,6,7 due to imprecision and indirectness | |

Treatment failure | 1.3 per 100 | 2.0 per 100 (0.3 to 6.4) | R.R. 1.57 (0.50 - 4.92) | 849 (3 cluster RCTs) | Very low 1,2,5,8 due to imprecision and indirectness | |

Tuberculosis mortality | 3 per 100 | 3 per 100 (1.3 to 6.75) | R.R. 0.99 (0.43 - 2.25) | 849 (3 cluster RCTs) | Low 1,2,3,5 due to imprecision | |

Long-term tuberculosis prevalence | 773 per 100,000 | 881per 100,000 (502 to 1546) | R.R. 1.14 (0.65 - 2.00) | 556,836 in 12 clusters (1 cluster RCT) | Very low 1,2,7,8 due to imprecision and indirectness | |

RR = Risk Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval; OR = Odds Ratio | ||||||

- No serious risk of bias: the studies were generally at low risk of bias. Not downgraded.

- No serious indirectness. The studies were done in high-prevalent tuberculosis settings in Africa (3) and Asia (1). The results could be generalized to other countries with similar tuberculosis burden and socioeconomic profile.

- Downgraded once for serious inconsistency. One study done in South Africa showed that the intervention detected fewer tuberculosis cases compared to no intervention. This cluster-RCT had fewer participants recruited from the farmer population, which may have a different risk profile compared to the general population and different from the other three cluster-RCTs. However, in a prespecified subgroup analysis by background tuberculosis endemicity in studies conducted in areas with a prevalence of 5% or more, heterogeneity was explained and the estimate became more precise (RR 1.52, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.09, 3 trials, 155,918 participants, moderate-certainty evidence).

- Downgraded once for serious imprecision. The 95% CI includes both clinically important effects and no difference for the effect of the intervention compared to control.

- Downgraded twice for serious imprecision. The 95% CI is wide and includes both clinically important effects and no difference for the effect of the intervention compared to control. The imprecision of the results could be due to small numbers of tuberculosis patients and number of tuberculosis patients with the outcome of interest. The studies were not powered enough to detect a difference between groups for the tuberculosis treatment outcomes.

- Downgraded once for serious imprecision. The 95% CI includes no difference for the effect of the intervention compared to the control group. The imprecision of the results could be due to small numbers of tuberculosis patients and number of tuberculosis patients with the outcome of interest.

- Downgraded twice for serious imprecision.

- Downgraded once for serious indirectness. The intervention arms had additional staff and procedures for following up patients on treatment. This may have a paradoxical effect of detecting more people who have treatment failure.

Relevance of the review for disadvantaged communities

Findings | Interpretation |

| Equity – Which of the PROGRESS groups examined |

|

| The trials included in this review were conducted in a mix of upper-middle-income countries (Brazil, Colombia, South Africa), middle-income countries (Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Zambia), and three low-income countries (Ethiopia, Nepal, and Zimbabwe), in both rural and urban settings. Undiagnosed tuberculosis is widespread in each of these countries.

| The review evaluates the effectiveness of different strategies to increase tuberculosis case detection through improved geographical, financial or educational access to tuberculosis diagnosis. While implictly relevant to PROGRESS groups, the trials did not consider PROGRESS groups in a disaggregated manner. Future research could examine whether some types of intervention are more or less effective for different types of PROGRESS groups, including intersectional impacts. |

| The effectiveness of active tuberculosis case detection across population subgroups was not explored in this review. | Active tuberculosis (with the development of symptoms, as opposed to latent tuberculosis) is strongly associated with immune system impairment due to illnesses such as HIV, diabetes and malnutrition. Future research could examine the effectiveness of active case detection interventions for patients with such co-morbidities. PROGRESS-related research could also related to population subgroups in which tuberculosis is widespread in high income countries, such as the Inuit in northern Canada. Future research could examine whether nutrition and poverty-related interventions may also improve tuberculosis case detection and decrease prevalence. |

| Equity Applicability |

|

| The effects of active tuberculosis case detection interventions are reliant on the practical details of implementation, such as the timing of visits. | The intervention effect might disappear or even reverse with different cultural norms, different attitudes toward tuberculosis, or different timing or settings for clinics or home visits. Futher, barriers to accessing tuberculosis diagnosis vary considerably between settings. Accordingly, programs need to be designed to fit local context. |

| The review summarized findings based on studies with a level of resources that may be greater than that available outside the research setting. | Factors to consider when assessing whether intervention effects are transferable to local settings include:

|

| Cost-equity |

|

| The studies included in the review did not report on the cost-equity of active tuberculosis case detection interventions. | The cost of these interventions may vary depending on the location and the costs per patient will depend on the health system and insurence providers. Economic context and affordability are important considerations. |

| Monitoring & Evaluation for PROGRESS Groups |

|

| It is unclear from the evidence whether active tuberculosis case detection interventions improve treatment success. It is also unclear from the evidence whether active tuberculosis case detection interventions reduce treatment failure, patients quitting treatment, or mortality.

| Further research is needed; in the meantime, many national and local decisions may be based on uncontrolled pilot studies demonstrating an acceptable number of confirmed tuberculosis cases resulting from an affordable intervention, which is periodically modified based on monitoring and audit. A more sensitive tuberculosis test (GeneXpertUltra) is currently being researched as a first screening tool for active case finding. Accordingly, the pool of studies will likely increase in the near future.

|

Comments on this summary? Please contact Jennifer Petkovic.

This summary was prepared by Karen Moore.